Updated 13 January 2025

It’s that time of year again, when fitness clubs cash in on the New Year surge. About 12 per cent of gym memberships are initiated in the month of January – that’s 25-30 per cent more than any other month. Unfortunately, the bloom comes off the ‘new year, new me’ rose fast for most, with half of new members quitting within the first six months. In all, an astonishing 67 per cent of people who are currently signed up for a gym membership, never actually attend.

One significant contributing factor to this annual gym membership boom-bust cycle is that most people have wildly unrealistic ideas about what exercise can do for them. In particular, they buy into the utterly false notion that exercising more is the key to losing weight. Despite consistent evidence that ramping up physical activity produces, at best, only modest weight loss, over 70 per cent of US adults believe that “exercise is a very effective way to lose weight”. Moreover, people who are overweight or obese and who hold this false belief, are at high risk of dropping out of an exercise program when their unrealistic expectations are not met.

Conversely, in my clinical experience, most people are tragically unaware of many, if not most, of the phenomenal benefits of exercise that are backed by extensive research.

I’m blessed to work with a highly self-selected segment of the population that has both a much greater awareness than the average ‘normie’ of the limitations (and frankly, the dangers) of the medical system, and a dramatically greater willingness to make significant diet and lifestyle changes in order to recover their health.

Increasingly, I’m seeing clients who are a practitioner’s dream: they are already eating nutritious wholefood diets and avoiding fluoride, PFAS, commercial cleaning and personal care products and the like, and hence they’re currently quite well. But they consult me because they want to ensure they’re doing everything they possibly can in order to maintain robust health so they can keep themselves out of doctors’ offices, hospitals and nursing homes as they age. Yet few even of these highly motivated people are doing enough physical exercise – and the right kinds of exercise – to achieve their goals. Clearly, they’re not intrinsically lazy people. They’re simply not adequately informed about the benefits of implementing a comprehensive exercise routine incorporating aerobic, strength, balance and flexibility training.

So, what are those benefits? For starters, people who regularly engage in physical activity slash their risk of developing the vast majority of conditions that erode quality of life and truncate lifespan, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, multiple types of cancer, and frailty and fragility fractures. That’s great, but it’s not enough to motivate most sedentary people to start exercising. What else does exercise do for us?

Perhaps the most overlooked and underappreciated benefits of physical activity are those relating to our minds. Exercise alleviates depression more effectively than SSRI antidepressants (without the nasty side effects, like sexual dysfunction that can persist even after you stop taking the drug), and reduces anxiety. It enhances cognitive performance by helping you learn faster and remember more, pay closer attention, and wield greater self-control over distractions. While regular exercisers exhibit improved cognitive functions, learning, and memory than non-exercisers, even a two-minute bout of moderate to intense exercise before undertaking a learning task improves attention, concentration, and learning and memory functions.

And, according to a study with an impressive 44-year follow-up period, the higher your level of physical fitness in midlife, the lower your risk of the disease that many aging people fear the most: dementia.

The study began in 1968, when 1462 Swedish women aged between 38 and 60 were recruited for the Prospective Population Study of Women (PPSW), a long-running cohort which has been used to examine many factors affecting health and survival, generating over 300 publications on topics ranging from sleep to sexual desire, and from dental health to diabetes.

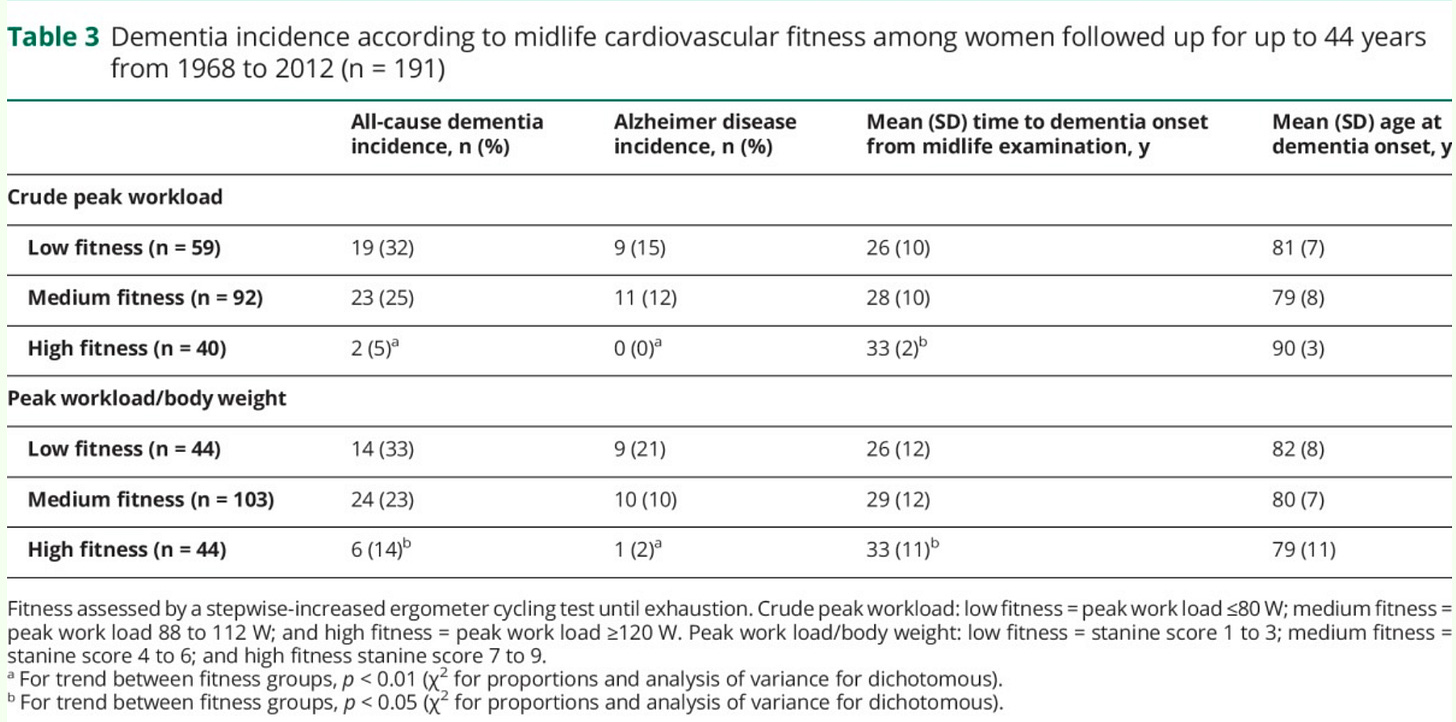

191 of these women participated in a cardiovascular fitness test which consisted of riding an exercise bike, with progressively increasing resistance, until they reached exhaustion. On the basis of their performance, the women were then classified into three categories: low, medium and high fitness.

Over the next several decades, the researchers administered periodic neuropsychiatric examinations to the women, and also used Sweden’s highly-centralised medical record-keeping system to track how many of them developed dementia. 23 per cent of the women were diagnosed with some type of dementia – Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, mixed dementia, or some other type – within the follow-up period from 1968 to 2012.

After adjusting for confounding factors such as age, education level, cigarette smoking, wine consumption, high blood pressure and diabetes, which are all known to affect dementia risk, a startling difference emerged: 32 per cent of women with low fitness in midlife developed dementia, while 25 per cent with medium fitness and only 5 per cent with high fitness did so.

Underlining the strong connection between heart health and brain health, of those whose fitness was so low that they couldn’t continue the cycling test past the warm-up phase because they developed ECG changes, chest pain, cramping or other signs of impaired cardiovascular function, a horrifying 45 per cent subsequently developed dementia. And conversely, precisely zero of the women who demonstrated the very highest level of fitness in this cohort – generating greater than 136 watts at peak workload, which isn’t even that high in the world of cycling enthusiasts – was diagnosed with dementia during the follow-up period.

Compared to women with medium fitness, those with high fitness were 88 per cent less likely to develop dementia, while those with low fitness were 41 per cent more likely.

Those with high fitness who did develop dementia were, on average, 11 years older at disease onset than those with medium fitness. That means they enjoyed over a decade more of fully functional, independent life before succumbing to dementia.

While it’s not yet clear exactly why a high level of fitness protects against dementia, the researchers point out that being fit reduces the risk of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, obesity and diabetes, all of which are known to contribute to dementia. Fitness-increasing activities also enhance neurotransmitter production and neurogenesis (growth of new brain cells, and formation of new connections between existing brain cells), which protect against dementia.

Of course, this is an observational study and hence can only show an association between fitness and dementia risk, not a causal link. Furthermore, as an editorial accompanying the study explained, fitness is largely determined by cardiac output (the amount of blood pumped by the heart in one minute), which is increased by exercise training, but is also strongly influenced by heritable factors. However, another study performed on a different subset of the same Prospective Population Study of Women cohort confirmed that physical activity in midlife (38–54 years) decreased the risk of developing dementia, again over a follow-up period of 44 years, suggesting that exercise truly does play a protective role.

In any case, what’s the downside of working on improving your fitness level? If you ramp up the frequency and intensity of your exercise sessions (under the guidance of an exercise physiologist or well-educated personal trainer, if you have any injuries or medical history that necessitates caution), you’re going to look, feel and function better in every way.

George Bernard Shaw famously quipped that “youth is wasted on the young”… and the same may be true for physical fitness. Take a look inside most gyms and you’ll see lots of young, fit people exercising vigorously, but as they get into their 40s and beyond, most people’s workouts have wound down considerably in intensity and frequency, or disappeared altogether.

Standard exercise programs for seniors consist of mild aerobic activity, light weights workouts and gentle stretching. They’re designed for people who haven’t put their bodies through their paces in any serious fashion for a good many years, as well as people who are recovering from a heart attack, joint surgery or other health challenge. Unfortunately, there is next to no progression built into these programs, and consequently the people participating in them never actually get much fitter – let alone, develop the level of fitness that was found to protect against dementia in the Swedish study.

Many middle-aged and older people seem to be frightened of exerting themselves to any serious degree. But provided there are no medical contraindications to intense exercise, and they receive proper instruction to avoid injury, and to ramp up their exercise intensity in a stepwise fashion, the risk of harm is incredibly low. Women, in particular, need to be performing strength training in order to counteract the aging-related decline in lean mass that leads to frailty – the leading risk factor for admission to a nursing home – yet mid-life and older women are the demographic that I have the most trouble persuading to take it up.

I don’t know about you, but I’m more afraid of developing dementia than I am of breaking a sweat! If pushing myself out of my comfort zone to improve my fitness is the price I need to pay to keep my brain healthy as I get older, I’m more than happy to pay it. And the reality is, once you’ve figured out a way to incorporate exercise into your daily routine, you’ll find you’re gaining benefits you didn’t anticipate – like deeper sleep, higher work productivity, brighter mood and enhanced self-efficacy which leads in turn to making better life choices.

The bottom line: Any exercise is better than none at all, but if you want maximum protection against dementia, a gentle daily stroll is not going to cut it. Find an activity that you enjoy that lends itself to ramping up the intensity over time, and a fitness professional to coach you if you need it. Your body will thank you for it, and so will your brain.

And for those of you who already have a solid exercise habit, feel free to share your fitness program, and tips for getting and staying motivated, in the comments section below.

One reply on “Are you fit enough to save your brain?”

I took up adult ballet classes at 48 two years ago. I was amazed at the age range of participants anywhere from 18 to 80, all levels of fitness and every shape and size. No judgement! Many of us had never been ballet dancers. It’s so great for the memory as well as balance and the strengthening of the muscles. Although I also enjoy the gym, I think dance is a wonderful way to exercise and encourage artistry with beautiful music!